Anatomy Moment: the shoulder girdle

Shoulders have been on my mind lately. Sometimes in the rehab and movement world we see themes in our clients, and lately our clients have been bringing us lots of shoulder puzzles. So thank you all — you know who you are! — for the inspiration of this Anatomy Moment.

What is the shoulder girdle? Let’s start with that often confusing word “girdle” – we’re not talking shape-wear here. Merriam-Webster’s defines girdle as “something that encircles or confines.” I LOVE this definition, in particular the image of encircling, as that is exactly what the bones that make up the shoulder girdle do: they cover a 360 degree range, encompassing the front, sides, and back of our trunk.

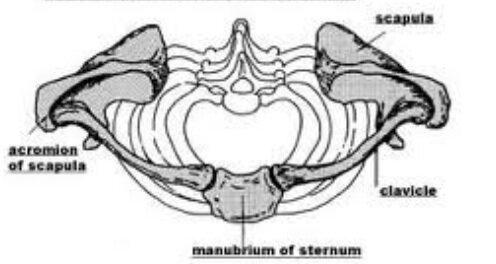

The bones. This picture is looking down on a skeleton, with the head and neck bones removed. The white bones in at the top center of the image which poke up are the vertebrae which make up the spine. The long white circular bones are the ribs. The shaded grey bones, with the exception of the central hexagonal bone on the bottom (we’ll get to that one later) make up the shoulder girdle.

The shoulder girdle is officially made up of six bones: a right and left clavicle (or collar bone), a right and left scapula (or shoulder blade), and a right and left humerus (or upper arm bone). These bones sit on top of our ribcage, much as a queen’s cape would sit on top of her torso. Imagine the collar bones as the strings which tie the cape in the front, and the shoulder blades and arms the heavy velvet which make up the cape. (Most of the cape is behind the queen, while some of it wraps around her sides. The side parts of the cape are analogous to our arms, the back of the cape to our shoulder blades.) Because the cape is one unit, any movement of one part will effect the rest:

If you tug the cape down in the back, the strings will pull upwards towards the neck. If you place your fingers on your collar bones, and then gently drag your shoulder blades downwards towards your hips, you should feel the collar bones gently rolling up towards your neck.

If you pull the sides of the cape forward around the body, the fabric on the back of the cape will stretch taught. Reach your arms as far forward as you can – really stretch them out, like you’re trying to grab something just out of your reach! You should feel a gentle stretch in your upper back.

If you were to lift the back of the cape up towards the back of the head, you would get a lot of scrunching of the fabric around the neck, and you may start to feel a connection between your “shoulder girdle cape” and your neck musculature.

Joints: the place where two bones meet. As mentioned in our foot post, where we have bones we have joints, and where we have joints we have movement. The joints of the shoulder girdle are unique, as they allow for a huge range of motion unseen anywhere else in the human body. The simple movement of raising your hand above your head actually involves movement at three joints!

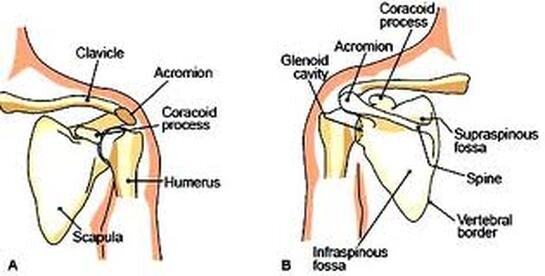

The first and most obvious joint is the glenohumeral joint. This is where the upper arm bone (or humerus) meets the shoulder blade. (Gleno- comes from the fact that the part of the shoulder blade which is in contact with the humerus is called the glenoid fossa.) If you raise your arm from your side to shoulder height, that’s a movement at your glenohumeral joint.

The next joint of the shoulder is the acromioclavicular joint, where the collar bone (or clavicle) meets the shoulder blade (particularly the acromion process of the shoulder blade). If you were to wear a coat with epaulettes — or maybe just a really good blazer from the 80s with some fantastic shoulder pads — the widest part of your coat would be about where your acromioclavicular joint is.

The third joint of the shoulder girdle is the sternoclavicular joint. If you find the widest part of your shoulder (right under that fantastic shoulder pad), and then trace the long, thin collar bone inwards towards your midline, right where the collar bone ends is the sternoclavicular joint, where the collar bone (or clavicle) meets the breastbone (or sternum).

Did anyone notice that we have another bone in play here??? The sternum, or breastbone, is the long flat bone in the center of the chest. It’s located about where a necklace would hang. Going back to this picture from earlier, it’s the hexagonal bone shaded grey in the center bottom of the drawing. It’s not an official part of the shoulder girdle, instead anatomists consider it part of the torso. Thus, this spot where the collar bone meets the sternum is where your shoulder girdle attaches to your trunk.

Find your sternoclavicular joint again, and then move your arm around. Raise it all the way up above your head, and then put it back down. Trace a big circle with your hand, all the way in front of you, all the way, up, all the way behind you and back down. You should feel some movement at your sternoclavicular joint. While the degree of movement is much less here than all the way out at your hand, you should feel some: the collar bone will raise and lower with the arm. We often don’t think of our shoulders starting this close to our midlines, but they do!

NOW! I would like to come back to the point that the sternum the ONLY boney connection between your shoulder girdle and your torso. That’s right. While the arm bone and shoulder blades have muscles which attach to the torso, the only boney connection your arm has to your trunk is that tiny sterno-clavicular joint. Amazing!

Why is this important? A boney connection, or joint, is supported by ligaments. Ligaments are tough, fibrous tissue which bind one bone to another. While they are designed to allow movement, their main job is to stabilize and support the joint. For the shoulder girdle, we only have one tiny joint — and one small set of ligaments — to support the wide range of motion our arms are capable of.

This wide range of motion our shoulders are capable of, supported by such a tiny boney connection, puts more of the jobs of stabilization and creating balanced movement on to our muscles. This is why balanced strength and flexibility throughout the musculature of the shoulder girdle is important, and why Pilates upper body strength work incorporates not just movement of the arm, but full range of motion of the shoulder girdle.

Let’s Move!

Book a group class or private session to use what you’ve learned: