Anatomy Moment: 52 foot bones

Feet have been on my mind lately. Many of my clients have foot pain, and just recently I got back to running after taking some time off due my own bout with it. I like to start my interest in a particular area with the anatomy – if we don’t know what’s there, it’s hard to be able to treat it! Way back in the beginnings of my anatomy geekiness, I was fascinated with the fact that a quarter of the bones of the human body are in our feet. There are 26 bones in each foot, adding up to a total of 52 foot bones. That’s a lot for such a small part of our body! If you don’t count the foot, the legs have just eight bones in them – four each. Quite the contrast. This month, I share my fascination with the architecture of our feet with you. The feet are our base, and as those of us living in earthquake-prone areas know, foundation is important.

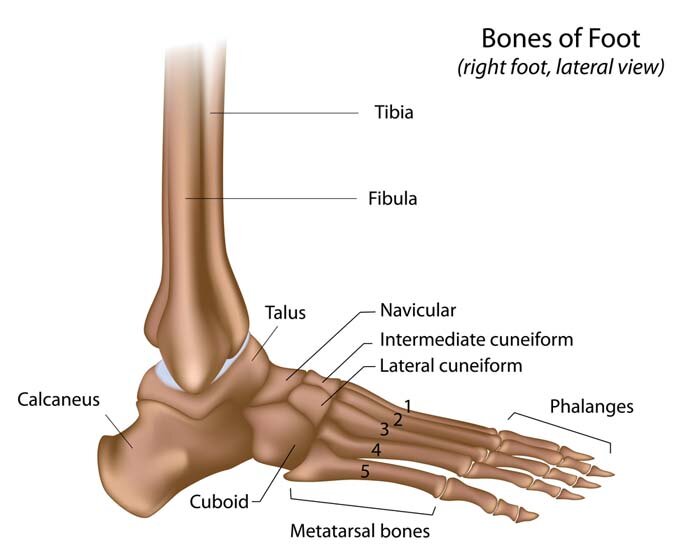

Name dem bones. Let’s start at the back of the foot, by the heel, and work forward, toward the toes. Here we go! If you grab your heel, you’re touching your calcaneus (1) – the heel bone is the largest bone in the human foot. What are those two nobs commonly referred to as the “ankle bones”? They’re actually part of the leg! Above the heel bone and below those two knobs, sits the talus (2). The talus is the true ankle bone, and is the only bone in the human body with no attachments to muscles. Traveling a little bit towards your toes, you have a group of five bones which, along with the calcaneus and talus, are collectively referred to as the “tarsals.” These five bones make roughly two rows, and form the majority of the arch of your foot. They are the: cuboid (3), navicular(4), lateral cuneiform (5), intermediate cuneiform (6), and medial cuneiform (7). Next up, we have the long bones of the foot, the “rays” which extend to the toes. These are collectively named the “metatarsals,” and their official singular names are simply the first metatarsal (8), second metatarsal (9), third metatarsal (10), fourth metatarsal (11), and fifth metatarsal (12).We’re only at 12, but we’ve covered most of the foot. Let’s plow through the toes, and, amazingly, we’ll get all 26 bones named! The structure of the big toe is a little different than the four smaller toes. The smaller toes have three bones a piece, while the big toe has only two. And yes, each bone has its own name. They follow a tedious naming structure which describes not only what toe the bone belongs to, but where it is in regards to the other bones of that toe:

—-> Big toe: proximal phalange of the first digit (13) and distal phalange of the first digit (14)

—-> Second toe: proximal phalange of the second digit (15), intermediate phalange of the second digit (16), and distal phalange of the second digit(17)

—-> Third/middle toe: proximal phalange of the third digit (18), intermediate phalange of the third digit (19), and distal phalange of the third digit(20)

—-> Fourth toe: proximal phalange of the fourth digit (21), intermediate phalange of the fourth digit (22), and distal phalange of the fourth digit(23)

—-> Little toe: proximal phalange of the fifth digit (24), intermediate phalange of the fifth digit (25), and distal phalange of the fifth digit(26)You’ve met them! Those are your 26 foot bones. Multiple by 2 for right and left, and you’ve got all 52. Now that you know who they are, why in the world do you need 52 foot bones?Why so many bones? Why do we have so many bones in such a small area of our bodies? The answer lies not in the bones, but in what exists in the spaces in between them: joints. Each foot contains 26 bones, connecting to make up 33 joints. While a bone is a stable, immobile structure, a joint is a possibility for movement.

Feet like to move it move it. Spread your toes. Scrunch your toes. Pull your toes up towards your head. Point your toes to the right, to the left. There’s a lot of possibility for different types of movement in our feet. In modern life, unless your feet are doing they’re own private hokey pokey, the purpose for all this movement possibility is not immediately apparent. However, if you think back to your latest hike and the variety of terrain you traversed, now there’s more of a reason for your toes to be able to go up, down, and side to side as your feet accommodate the changing terrain of the trail. If you were a prehistoric person covering that same terrain to gather food for the day, your feet wouldn’t be wearing shoes, and they would have to mold to the ground to allow for balance and propulsion. All of those joints in the feet allow us to walk over stones and sticks, clamber over logs, balance on river rocks, AND take long, romantic walks on the beach. In fact, there are muscles in our feet which only work when we are barefoot.

How does Pilates work with the feet? Chances are, if you’ve come in to see us for foot pain, knee pain, hip pain, or even lower back pain, your instructor has had you do some exercises for your feet. When we wear shoes all day and walk on flat ground, our feet don’t get much movement in those 33 joints. The result is that they’re often stiff or immobile. Stiffness in a joint due to lack of motion is often accompanied by weakness in the muscles which are in charge of creating that motion. This means that most of us, just due to the standards of modern life, have both stiff and weak feet. If you have a great house on a poor foundation, things may not look so great after an earthquake, and if you have a strong core and legs on top of weak and inflexible feet, you may still feel pain or discomfort after putting your body through the stresses of a run or hike. That ability of your feet to mold to the ground is critical for keeping stress out of the joints “up the chain” from your feet – your knees, your hips, and your lower back. Thus, traditional Pilates repertoire views restoring the mobility and strength of the feet as key to restoring the alignment for the rest of the body. The first thing you do once you come into the Pilates studio is remove your shoes, getting those muscles that only work when barefoot active. Depending on your needs, your instructor may have you roll your feet on a pinky ball, stretch your calves, use the “Foot Corrector,” do footwork on the reformer, work on holding onto the straps in feet in straps on the springboard, perform some ankle isolation on the chair, and a myriad of other exercises.

Don’t I just need better shoes for my feet? What about orthotics? In some instances, yes, shoe choice and orthotics can be helpful and can provide a temporary needed support or correction to help alleviate your foot pain. However, if I thought that shoes would permanently fix the problem, I would be a shoe salesman. Weakness and immobility in the feet is primarily caused by not getting enough movement during the day, a problem which is made worse by stiff or immobile shoes. Unless you are working with an acute injury that needs support while it heals, I don’t think that orthotics or super supportive shoes are a solution which helps combat the original dysfunction which lead to the pain. If we restore the natural mobility and strength of your feet, you’ll have your own muscular arch support, and you won’t need to pay for an orthotic or a shoe to do it for you.If you want to read more about how to restore your feet to better health, I strongly recommend Whole Body Barefoot by Katy Bowman.

What can I do at home? Take your shoes off! Spend some time barefoot to get those muscles workin’. Roll your feet on a ball. Put a small half roller in front of the bathroom sink and stretch your calves while you brush your teeth. Spread and wiggle your toes around while you watch TV, or wear yoga toes. Or, skip the TV and take a (barefoot) romantic walk on the beach instead.(These are not ads or affiliate links. These are products I use, find helpful for many clients, and think are easy to integrate into daily life. Get ’em if you want ’em, and enjoy!)

Let’s Move!

Book a group class or private session to use what you’ve learned: